If you’re a podcast listener and generally into health and fitness, I’d be surprised if you haven’t heard of the Huberman Lab. Originating from Stanford University, under the direction of neuroscientist Dr. Andrew Huberman, the Huberman Lab released a podcast in 2021 which has become on the of the most listened-to shows in the world. In fact, it’s been consistently ranked #1 in the categories of Science, Education and Health & Fitness and currently boasts 2.8 million subscribers.

According to Dr. Huberman, the mission of the podcast is to provide “zero-cost information about science and science-related tools” with the goal of explaining how the brain controls our perceptions, behaviours and health, as well as measuring and impacting the nervous system. The research and tools presented cover many areas of interest, including enhancing sleep quality, improving physical fitness and cognitive ability, maintaining motivation and reducing levels of anxiety. You can check out an example of one of the podcast episodes here:

In many cases, Huberman interviews other scientific experts in the area he wishes to discuss. Past interviews have included Dr. Alicia Crum, a tenured Professor of Psychology at Standford (see video above) and Dr. Wendy Suzuki, a Professor of Neuroscience and Psychology at NYU. In a world where so much of our information comes from unreliable sources, it is encouraging to know that experts like these are reaching almost 3 million subscribers! To me, it’s an excellent example of translational research in action. Huberman is providing the public with science-backed tools that are accessible, easy to implement and can have a direct positive impact on their lives.

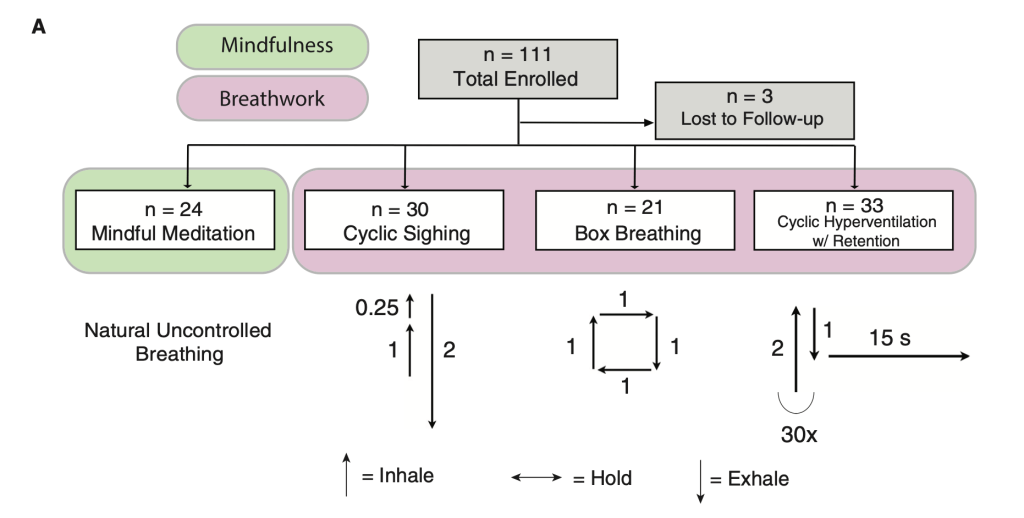

I can personally attest to one of Dr. Huberman’s recommendations, which is backed by a study he and Dr. David Spiegal published in the open-access journal, Cell Reports Medicine, entitled Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. The study is a remote, randomised, controlled study looking at breathwork practices as potential tools for stress management and well-being. In the study, three different daily 5-min breathwork exercises are compared with a 5-min mindfulness meditation practice over one month. The breathwork exercises include cyclic sighing (i.e. prolonged exhalations), box breathing (i.e. equal duration of inhalations, breath retentions and exhalations) and cyclic hyperventilation with retention (i.e. longer inhalations and shorter exhalations). Both improvement in mood as well as reduced physiological arousal (i.e. respiratory rate, heart rate and heart rate variability) were used to gauge the results of either technique, through tools such as the WHOOP tracker and two online questionnaires – the State Anxiety Inventory and the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – delivered to participants before and after completing their daily exercises. You can see the experimental set-up and the sample sizes in the figure below:

Whilst both the mindfulness meditation and the breathwork groups showed significant reductions in ‘state’ anxiety (i.e. transitory emotional state consisting of apprehension, nervousness, an increase heart rate, etc.), breathwork and specifically cyclic sighing was the most effective tool for increasing overall positive affects, as can be seen in the figure below:

Indeed, breathwork specifically produced a significantly greater reduction overall in respiratory rate and a higher daily increase in positive affects over the course of the study. Since hearing about these results, I’ve started combining deliberate breathing exercises alongside my daily meditation practice over the last few weeks or so and can certainly say it’s had a positive overall impact on my life! You can see more of the Huberman Lab’s publications here.

It’s important to note that the Huberman Podcast certainly wasn’t the first and nor is it the only example out there of everyday simple, fast-acting and cost-effective translational research in action. You can find several other examples of scientists or doctors taking their research from the lab to the public below, including Professor Matt Walker ‘s Sleep Podcast and cardiologist Dr. Sanjay Gupta’s YouTube channel, York Cardiology.