From vaccines to solar cells, the kind of tech we need to solve some of the world’s biggest problems tends to be generated in labs by scientific researchers with ‘Doctor’ in front of their names. However, in the UK, only 0.5% of STEM PhD students choose to license or spin-out their research every year into usable products or services [1]. Whilst this figure may seem unnaturally low, it is actually a relatively unsurprising statistic, given that the inherent aim of the PhD is to uncover novelty, as opposed to create a scalable venture. Indeed, according to my conversations with researchers and experience in early-stage science, in most places, building a venture out of PhD research is at best an afterthought and at worst, a major inconvenience and distraction.

It all tracks back to the early incentives that these projects are built on. Typically, those incentives tend to be focused on publishing research in high-impact scientific journals – a feat which is often so highly-rewarded in academia. Indeed, it is hardly a secret that frequent publication of research tends to demonstrate academic talent and brings positive attention to scholars and their institutions, particularly in terms of grant funding. To achieve this kind of research often means uncovering scientific novelty – critical to expanding our knowledge of any one field – as opposed to uncovering simple and straightforward ‘value’, so to speak. The ‘publish or perish’ cycle is summarised nicely in the figure below:

Since incentives tend to drive outcomes, it makes sense that most PhD students are encouraged to focus on achieving exciting, publishable results, as opposed to the wider scalable value of their research. The situation is further complicated by the fact that the PhD has historically been built to train (and recruit) our future tenured academics. Think about it – you’re conducting lab research (often individually), analysing data, writing up your findings in a 300-page dissertation, completing government grant proprosals, presenting the core science of your work at academic conferences and learning how to juggle the academic ladder. And whilst there’s certainly elements of a PhD that lend themselves well to entrepreneurship (i.e. plenty of independence, the need to pivot and ‘pitch’ for funding), it’s hard to argue against the clear pathway into a postdoc, PI and beyond. Indeed, according to a 2020 study by the Higher Education Policy Institute, PhD students feel well-trained in analytical-thinking, data and technical skills, along with presenting to specialist audiences and writing for peer-reviewed journals [2]. However, they are far less confident in managing people, applying for funding and managing budgets – all key parts of launching a venture.

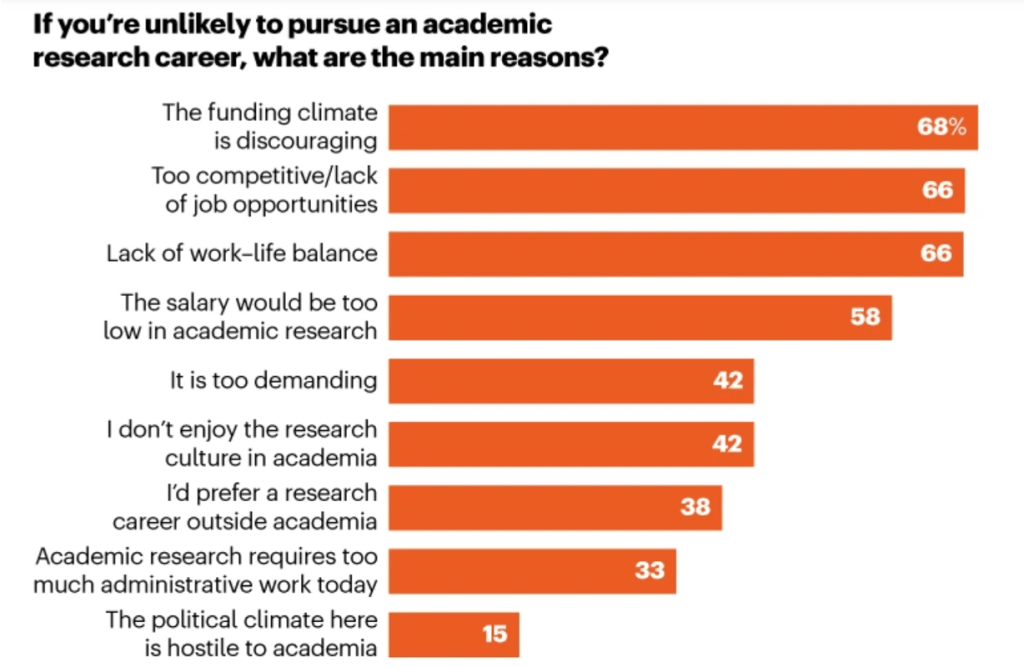

Now what’s also interesting, is that while 67% of PhD students want to become tenured academics, only 30% actually remain in academia three years on, despite being rigorously trained to become academics [2]. Some of the reasons why graduate students are unlikely to pursue an academic research career are summarised in the plot below, taken from a 2022 Nature article entitled‘I don’t want this kind of life; graduate students question career options’ [3].

To me, this seems like a lost opportunity to seize the significant value to our society that these highly-trained students and their research can offer. I therefore think it’s worth pursuing a so-called ‘split’ PhD, in line with what editor Julie Gould suggested in her 2015 Nature piece entitled ‘How to build a better PhD’. According to Gould, there are currently too many PhD graduates for academia [4]. In other words, there is a mismatch between the number of PhD graduates and the number of available secure academic positions for those graduates, which explains why so many are forced to leave. As such, we should consider splitting the PhD in two – ‘one for future academics and a second to train those who would like in-depth science education for use in other careers’, says Gould. Whilst students in the academic-track PhD might focus on blue-skies research and discovery, the ‘vocational’ PhD would be more structure and directed towards areas such as machine-learning or radiography, for instance.

There are versions of this split which already exist, such as the EngD in the United States and Germany, which is a Doctorate in Engineering focusing on solving complex, industry-focused problems. There’s also the industrial PhD, in which private-sector companies will pay and employ students who are simultaneously enrolled in a university program to conduct research on their behalf.

Whilst these are two excellent options for more industrially-minded students, I am most excited by the new ‘flavour’ of PhD very recently introduced by London-based venture creator and investment firm, Deep Science Ventures. DSV’s new Venture Science Doctorate is reportedly diversity-first, venture-focused and directed towards two main themes – either building global climate resilience or advancing healthcare through venture creation [5]. Over a three year program, the candidates will take on a project ranked by impact and feasibility, enter the lab, begin research and prototyping and finally, incorporate a company and raise seed investment. On top of creating a new company, the students will also publish a (supposedly modified) thesis, policy whitepaper and investment memo. They posted a webinar on it which you can find here and you can see the program outline below:

What I love (so much!) about this program is it’s direct focus on shifting incentives early on from creating something novel to be published towards creating something of value to be commercialised, for the benefit of those venture-minded scientists (and our society as a whole). Current supporters include Thomas Kalil, the former Deputy Director for Technology and Innovation at the White House and Priya Guha, MBE, a Venture Partner at Merian Ventures and Board member at UKRI. By 2026, DSV aims to have trained their first 10 PhD candidates, who will have incorporated a company each in the healthcare or climate space. You can read more about it here.

Of course, it’s important to note that programs like the Venture Science Doctorate should not be meant to replace the PhD. Instead, the goal would be to put forward an alternative to the current programs on offer. The fundamental research done by traditional PhDs is also imperative – but my focus here (and passion) is on translational research!

It would be great to hear thoughts from others in the field around the idea of splitting the PhD and the different flavours it could take.

References:

[1] Are British universities holding back tech spin-outs with unreasonable equity demands?

[3] Woolston C. ‘I don’t want this kind of life’: graduate students question career options. Nature. 2022 Nov; 611(7935):413-416. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-03586-8. PMID: 36344617.

[4] Gould J. How to build a better PhD. Nature. 2015 Dec 3;528(7580):22-5. doi: 10.1038/528022a. PMID: 26632571.